Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System

As we know from Wikipedia, stress testing is a form of testing that is used to determine the stability of a given system or entity. It involves testing beyond normal operational capacity, often to a breaking point, in order to observe the results. The concept is quite fashionable nowadays; it has reached mainstream in the context of the financial sector and even when making an assessment of operational characteristics of a railway station.

Now it looks as if we shall be witnesses of something that comes near to a major stress testing exercise of the patent system.

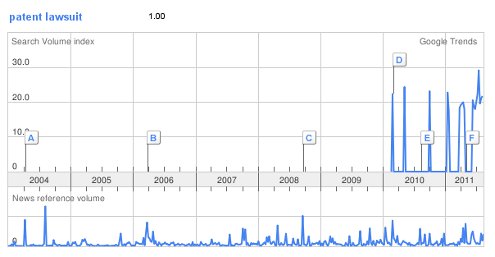

We all are supposed to be aware that an awful lot of litigation is currently going on in the field of mobile devices like smartphones and tablet computers. Reuters have published nice infographics on patent-related suits between mobile device / component manufacturers here. Moreover, there are press reports saying that Apple, Inc., is about to launch another patent based suit against Samsung allegedly aiming at a EU wide ban on all of Samsung’s smartphones and tablet computers under its Galaxy brand. If these speculations were true and if Apple were to prevail in such battle, the suit could not only be a blow to Samsung but also to the Android ecosystem in its entirety.

Another litigation front has been opened by a company named Lodsys, a non-pracitcing entity (NPE) suing certain individual software developers who brought to market smartphone apps which allegedly are infringing Lodsys’ patent rights.

It appears to be quite clear that the motivation of Google to acquire Motorola Mobility for USD 12,5 billion is mostly fueled by their desire to overcome a perceived inferiority of their own patent portfolio.

In general, patent litigation has ever been a relatively rare incident. All over Europe each year there a few thousand new patent litigation cases that get started; some details covering the years before 2006 have been compiled on behalf of the EU Commission when mooting a mandatory insurance scheme (1, 2). This appears not to be much in view of the fact that hundreds of thousands of patent applications are filed per year. Many of such litigation cases eventually get settled.

Although the outcome of some of those cases is perceivable for businesses seeing themselves barred from implementing and/or importing certain patented technologies, general public and consumers normally are not much aware of patent squabbles. If, as a result, license fees are to be paid, intransparency of cost structures normally prevents consumers from getting clear view of IP related costs. And, it might be not clear if there are any precedents where broader consumer circles got widely aware that they were not able to buy a certain desired product because of patent infringement problems.

But what would happen if for broader consumer circles desiring to go shopping for a new mobile device it becomes transparent that on the world market there are many other offerings available which he or she is denied access solely on the grounds of intellectual property infringement?

If, for example, Apple would prevail and obtain an injunction across Europe banning the import of a broad range of Android based mobile devices manufactured by Samsung, the case surely will get a lot of publicity in mainstream media. The same holds, on a smaller scale, if popular smartphone apps are retracted from market solely due to patent problems. Other examples might be easily at hand.

A big question appears to be as to how the political impact of such scenario will develop. E.g., those consumer circles preferring Android based devices over Apple products might feel deprived of something they legitimately should be able to buy for their money. In the overall effect, such situation might put stress on the political acceptance of the patent system as we know it today.

The scenario even might evolve into sort of a litmus test for the acceptance of the current system of intellectual property protection in general and patent law in particular. If, in such a scenario, mainstream media and technical magazines addressing interested parts of the public take a view that such non-availability of certain products is not the logical consequence of legitimate merits of the patent proprietor but result of an alleged failure of the patent system, things might get instable.

This week The Economist, an institution not known for any anti-capitalist propaganda, writes in its print edition:

In recent years, however, the patent system has been stifling innovation rather than encouraging it. A study in 2008 found that American public companies’ total profits from patents (excluding pharmaceuticals) in 1999 were about $4 billion—but that the associated litigation costs were $14 billion. Such costs are behind the Motorola bid: Google, previously sceptical about patents, is caught up in a tangle of lawsuits relating to smartphones and wants Motorola’s huge portfolio to strengthen its negotiating position.

Earlier this year, Google General Counsel Kent Walker wrote an article in The Official Google Blog, saying:

The tech world has recently seen an explosion in patent litigation, often involving low-quality software patents, which threatens to stifle innovation.

Hence, it cannot be assumed that the establishment (whatever exactly that might be) is actually unanimously supporting the current shape of the patent system.

During the years 2000 to 2005 the has been a strong public debate about a proposed sectoral Draft EU Directive regulating patentability of computer-implemented inventions aka ‘software patents’. On September 24, 2003, a movement of patent critics initialised by FFII (and later fostered by Florian Müller’s NoSoftwarePatents campaign) nearly prevailed in pushing certain parliamentary groups in a plenary vote in the European Parlament to wreck the entire system of European patent law. Only after the entire Draft EU Directive had been abolished in 2005, the discussion died down.

In the meantime, interested circles have continued a discussion on restrictions of patent law. On the one hand there are groups continuing to argue against sectoral patentability of computer-implemented inventions. As there appears no realistic chance for a revival of any legislative initiative to ban patents on computer-implemented inventions, some say that the European Patent Office, run by the European Patent Organisation which is an organisation based on an international treaty, the European Patent Convention (EPC), but not on the EU Treaties, should be brought under control of the EU, see e.g. the campaign website www.unitary-patent.eu. They believe that EU might have a more tight grip on the European Patent Office. On the other hand, there are authors like Glyn Moody who are advocating abolishment of the entire patent system.

It appears as if all these groups and individuals do not have much traction in mainstream media at the time being. However, if patent litigation gets epidemic in areas where broader consumer circles feel the consequences, this might well change. Recent polls say that the Pirate Party known for their critics on the system of intellectual property might get a 4.5 % share of the votes on the upcoming elections for the Parliament of the State of Berlin in Germany which is due on September 18, 2011. If they manage to improve up to at least 5%, they will win seats. Of course, the Berlin State Parliament has no legislative power with regard to intellectual property legislation in Germany but the upcoming development might show some volatility of the current political situation with potential effects also with regard to future legislation on intellectual property matters.

It is evident that there is a bulwark of international treaties, namely TRIPS, defining minimum standards of intellectual property protection. On EU level, Directive 2004/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the enforcement of intellectual property rights (also known as “(IPR) Enforcement Directive” or “IPRED”) is to be mentioned here defining EU standards for intellectual property enforcement. Potentially ACTA might, after ratification, be added to this list. These international commitments make it very hard to alter any of the core ingredients of the contemporary system of intellectual property law. They are, hence, a stabilising factor of the status quo. However, of course these provisions can be altered at any time provided that sufficient majorities get organised in multiple countries to accomplish this. In this context it appears to be relevant that a significant portion of discontent over the present system of intellectual property law now comes from the United States, currently the global major player in view of maintaining and strengthening IP laws. This is different in view of the former 2000 – 2005 row over the EU Directive on patentability of computer-implemented inventions which was confined to Europe and mostly supported from German, French, and Italian NGOs.

For example, from time to time proposals are made to shorten the term of protection of software patents. Apart from the question if such move makes sense at all, Article 33 of TRIPS makes clear that no WTO Member State is free to take such measures without amending this code:

The term of protection available shall not end before the expiration of a period of twenty years counted from the filing date.

Hence, it would be difficult to implement a measure recently suggested in The Economist:

First, patents in fields where innovation moves fast and is relatively cheap—like computing—should have shorter terms than those in areas where it is slower and more expensive—like pharmaceuticals. The divergent interests of patent-holders in different industries have held up reform, but there is no reason why they should not be treated differently: such distinctions are made in other areas of intellectual-property law.

So, if confidence of larger portions of the general public in the proper working of the patent system gets damaged by ongoing and upcoming patent battles, a nasty situation might result where significant portions of the society unite in demanding alterations of the system of intellectual property laws where the Governments so addressed are not in a position to give way without breaching international law. Such trap might be dangerous in a broader political context because of it might strengthen general feelings of discontent of the general public in relation to the undertakings of the respective political class.

Even if the current peak of patent battles on the field of smartphones and tablet computers eventually dies down, it appears to be quite clear that computer software, not biotechnology or nanotechnology, will remain the main driver of transformation of our economy for the coming years. Marc Andreessen, board member of HP, Facebbok and eBay, recently wrote an interesting article on Wall Street Journal titled Why Software Is Eating The World . He writes:

My own theory is that we are in the middle of a dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies are poised to take over large swathes of the economy.

His reasons are as follows:

More and more major businesses and industries are being run on software and delivered as online services—from movies to agriculture to national defense. Many of the winners are Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurial technology companies that are invading and overturning established industry structures. Over the next 10 years, I expect many more industries to be disrupted by software, with new world-beating Silicon Valley companies doing the disruption in more cases than not.

So, if Marc Andreessen is right, we surely will see still more controversial discussions about sectoral patenting issues in the field of software patents.

(Photo (C) 2010 by jon smith ‘una nos lucror’ via Flickr and licensed under the terms of a CC license)

Axel H. Horns

German & European Patent, Trade Mark & Design Attorney

6 Responses to Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System

The k/s/n/h::law blog

Some of the patent attorneys of the KSNH law firm have joined their efforts to research what is going on in the various branches of IP law and practice in order to keep themselves, their clients as well as interested circles of the public up to date. This blog is intended to present results of such efforts to a wider public.

Blog Archives

- November 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (5)

- March 2013 (5)

- February 2013 (4)

- January 2013 (5)

- December 2012 (5)

- November 2012 (5)

- July 2012 (5)

- June 2012 (8)

- May 2012 (5)

- April 2012 (3)

- March 2012 (4)

- February 2012 (5)

- January 2012 (6)

- December 2011 (12)

- November 2011 (9)

- October 2011 (9)

- September 2011 (4)

- August 2011 (7)

- July 2011 (4)

- June 2011 (1)

Blog Categories

- business methods (6)

- EPC (7)

- EPO (12)

- EU law (92)

- ACTA (8)

- CJEU (4)

- Comitology (1)

- competition law (2)

- Enforcement (6)

- EU Unified Patent Court (62)

- FTA India (1)

- TFEU (2)

- Trade Marks (5)

- European Patent Law (37)

- German Patent ACt (PatG) (1)

- German patent law (5)

- Germany (6)

- Pirate Party (3)

- International Patent Law (4)

- PCT (2)

- IP politics (10)

- licenses (2)

- Litigation (5)

- Patentability (7)

- Patents (12)

- Piratenpartei (2)

- Software inventions (10)

- Uncategorized (9)

- Unitary Patent (24)

- US Patent Law (4)

Comments

- kelle on Germany: Copyright Protection More Easily Available For Works Of “Applied Arts”

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days - KSNH Law - Intangible.Me on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days | ksnh::law on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Cou... on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- European Commission Takes Next Step Towards Legalising Software Patents in Europe | Techrights on EU Commission publishes Proposal of amendend Brussels I Regulation for ensuring Enforcement of UPC Judgements

Blogroll

- 12:01 Tuesday

- America-Israel Patent Law

- Anticipate This!

- AwakenIP

- BlawgIT

- BLOG@IPJUR.COM

- BP/G Radio Intellectual Property Podcast

- Broken Symmetry

- Class 46

- Director's Forum: David Kappos' Public Blog

- Gray on Claims

- I/P UPDATES

- IAM Magazine Blog

- Intellectual Property Intelligence Blog

- IP Asset Maximizer Blog

- IP CloseUp

- IP Dragon

- IP Watch

- IP Watchdog

- IPBIZ

- ipeg

- IPKat

- ITC 337 Law Blog

- Just a Patent Examiner

- K's Law

- MISSION INTANGIBLE

- Patent Baristas

- Patent Circle

- Patent Docs

- Patently Rubbish

- PatentlyO

- Patents Post-Grant

- Reexamination Alert

- SPICY IP

- Tangible IP

- The 271 Patent Blog

- The Intangible Economy

- THE INVENT BLOG®

- Think IP Strategy

- Tufty the Cat

- Visae Patentes

The KSNH blogging landscape

This blog and the German-language sister blog k/s/n/h::jur link to the two popular and privately run blogs IPJur und VisaePatentes and continue their work and mission with a widened scope and under the aegis of our IP law firm.

ksnhlaw on Twitter

- No public Twitter messages.

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013Auf verschiedenen Feldern beruflicher Praxis ist dafür zu sorgen, dass Kommunikation vertraulich bleibt. Die trifft beispielsweise für Ärzte zu, aber auch für Anwälte, darunter auch Patentanwälte. Einer der zahlreichen Aspekte, die in diesem Zusammenhang eine Rolle spielen, ist die Technik, um die Vertraulichkeit beruflicher Kommunikation sicherzustellen. Wa […]

- EU-Einheitspatent: Demonstrativer Optimismus und Zahlenmystik allerorten – Naivität oder politische Beeinflussung? June 26, 2013Nach mehreren vergeblichen Anläufen zur Schaffung eines EU-weiten Patentsystems wurde 1973 als Kompromiss das Europäische Patentübereinkommen unterzeichnet, welches unabhängig von der seinerzeit noch EWG genannten Europäischen Union System zur zentralisierten Patenterteilung mit nachgeordnetem Einspruchsverfahren durch das Europäische Patentamt schuf. Wie wi […]

- Moderne Zeiten oder: DPMA und Patentgericht streiten über die elektronische Akte April 25, 2013Bekanntlich hat das Deutsche Patent- und Markenamt (DPMA) im Jahre 2013 mit der rein technischen Fertigstellung der Einrichtungen zur elektronischen Akteneinsicht einen wichtigen Meilenstein seines Überganges von der Papierakte zur “elektronischen Akte” erreicht. Im DPMA werden aber bereits seit dem 01. Juni 2011 Patente, Gebrauchsmuster, Topografien und erg […]

- Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013 March 11, 2013Unter dem Datum vom 28. Februar 2013 ist die Bundestags-Drucksache 17/12611 veröffentlicht worden Sie trägt den Titel Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung - Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013. Die Bundesregierung legt dem Deutschen Bundestag seit dem Jahr 2008 […]

- 3D-Printing: Zum Filesharing von 3D-Modelldaten February 25, 2013In meiner kleinen zuvor angekündigten Reihe über rechtliche Aspekte des 3D Printing komme ich heute auf die Frage zu sprechen, ob die Hersteller von Gerätschaften es hinnehmen müssen, wenn Ersatztreile davon – vom Brillengestell über Smartphone-Gehäuseteile bis hin zu Rastenmähermotor-Abdeckungen – gescannt und die daraus […]

- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013

[...] Read this article: Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System | ksnh … [...]

[...] Continue reading here: Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System … [...]

[...] Here is the original post: Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System … [...]

[...] original post here: Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System … Tags: apple, based-devices, big-question, feel-deprived, ffii, florian, nearly-prevailed, [...]

I share your perception, and have written the same thing in “Grenzen des Patentwesens” 10 years ago: Patent professionals should be the first objecting to abusing the system, since that will lead to opposition.

The question you don’t address in your post is: What do you want to do about it? Once software patents are issued, is there any way to stop people from actually using their rights?

I might also mention that “stress tests” now are also done for nuclear power plants, to which my interest has shifted lately. You probably don’t want a public perception of the patent system equal to that of nuclear energy in Germany.

[...] post by Axel Horns here. He seems to be worried about a possible backlash from the abuse of the patent system happening in [...]