After the last-minute amendments of the Unitary Patent Regulation (UPR) by the European Council on 28/29 June, who suggested

that Articles 6 to 8 of the Regulation [...] to be adopted by the Council and the European Parliament be deleted

lead to a removal of this matter from the EU Parliament’s agenda and unleashed a wave of revulsion among members of the EU Parliament in general and those of its legal committee (JURI) in particular (see here and here), the direction in which today’s JURI meeting would go was not utterly hard to predict.

And in fact, today’s press release confirmed what could have been expected anyway:

The European Council’s move to change the draft law to create an EU patent would “infringe EU law” and make the rules “not effective at all“, Bernhard Rapkay (S&D, DE), who is responsible for the draft legislation, told the Legal Affairs Committee on Tuesday. Most MEPs strongly criticised the European Council’s move and agreed to resume the discussion in September.

Apparently, this opinion is backed by the Parliament’s legal service, assuming that deleting Articles 6 to 8 UPR would “affect the essence of the regulation” thus be incompatible with EU law.

On an Official blog website blogfraktion.de of the parliamentary group of the Christian Democratic Union / Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) in the German Bundestag I recently stumbled upon a green paper concerning copyright in the digital society (Diskussionspapier der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion zum Urheberrecht in der digitalen Gesellschaft) presented by Deputy Party Whips Mr Michael Kretschmer and Mr Günter Krings. While the main topic of this text, of course, is directed to copyright issues, we also can find a single paragraph devoted to so-called software patents or, more technically, patents on computer-implemented (respectively implementable) inventions as follows (I did some plain copy/paste operation and refrain from correcting spelling errors in the German original):

8. Urheberrecht statt Softwarepatenten

Computerprogramme werden richtigerweise durch das Urheberrecht geschützt. „Softwarepatente“ auf Quell-Codes laufen dem urheberrechtlichen Schutzzweck zuwider. Der urheberrechtliche Schutz ist flexibler und innovationsfördernder, weil dazu kein aufwendiges und teures Patentierungsverfahren notwendig ist. Die Anwendbarkeit des Urhebervertragsrechts stärkt außerdem die Programmierer (Urheber) gegenüber den Softwarefirmen (Verwertern).

Ein Richtlinienvorschlag der EU-Kommission, eine EU-einheitliche Patentierungspraxis für Software zu schaffen, ist 2002 gescheitert. Die CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion lehnt auch weiterhin jede Ausweitung der Patentierungspraxis im Softwarebereich ab.

I would like to offer my own translation as set out below:

8. Copyright instead of software patents

Computer programs are rightly protected by copyright. “Software patents” on source code run contrary to the purpose of protection by copyright. Protection by copyright is more flexible and encourages innovation more because it does not require intricate and expensive patenting proceedings. Moreover, the applicability of the [German] law of contracts on copyrights strengthens the coders (creators) compared to software companies (exploiters).

A Draft proposal of the EU Commission for creating a unitary practice of patenting of software has failed in 2002. The parliamentary group of the CDU/CSU in the Bundestag maintain their rejection of any broadening of the practice of patenting in the field of software.

The first sentence of this statement asserting that computer programs are rightly protected by copyright is one of the few snippets of information from the text as quoted above which is by and large correct insofar historically the Council Directive 91/250/EEC of 14 May 1991 on the legal protection of computer programs had stipulated in its Article 1 that Member States shall protect computer programs, by copyright, as literary works within the meaning of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. However, the term “rightly” (“richtigerweise” in German) might, at least for German ears, be construed like suggesting that software protection by copyright is the only (proper and legitimate) way to define software-related Intellectual Property. This is not true. Article 9 paragraph 1 of the Directive says (emphasis added):

The provisions of this Directive shall be without prejudice to any other legal provisions such as those concerning patent rights, trade-marks, unfair competition, trade secrets, protection of semi-conductor products or the law of contract. [...]

In the next sentence: “Software patents” on source code run contrary to the purpose of protection by copyright, a stark theory is proclaimed deepening this initial stub of mis-understanding the law by setting forth in more detail there is sort of a contradiction between copyright and patent law. In fact, copyright law and patent law are mapped to different aspects of computer software, respectively:

- From a copyright-centred point of view, a computer program is seen as a text (source code).

- From a patent-centred point of view, a computer program is seen as an expression of functionality or of dynamic semantics described by operational and/or denotational semantics, i.e. it is viewed as an expression of run-time behaviour.

Copyright and patent rights can emerge from one and the same set of facts of a case. This phenomenon is not confined to copyright and patent law concerning software. Take, for example, a mud wing of a car:

Continue reading »

Anti-Patent Campaigners put their trust in François Hollande as EU Council attends to Unitary Patent Court again

The newly elected President of France, François Hollande promising "change". Will he be the first anti-patent campaigner governing an EU state?

Now that François Hollande took office as the new President of France after his marginal victory in the French presidential elections this May, he will now introduce himself to official EU policy on his first Competitive Council meeting on May 31/June 1. The draft agenda for this meeting (cf. item 19), reading “Draft agreement on a Unified Patent Court and draft Statute – Political agreement“, electrifies observers of and parties involved the ongoing European patent legislation saga (see also press release, middle of page 5).

In recent months the upcoming French elections brought the negotiations on the Unified Patent Court Agreement to a complete standstill, as the dynamics between the French, British and German heads of govenment and the general political climate is a crucial factor in this legislative process, especially since the only serious and realistic candidates for the attractive seat of the new UPC Central Division are Paris, London, and Munich and it is frequently announced through official channels that this question is the only remaining open issue.

The EU Council expressed already in January this year its believe that a final agreement can be reached in June 2012 (see official statement) and it was the President of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, who clarified in a recent letter that he hopes (or expects) the remaining issues to be sorted out at next week’s Competitiveness meeting:

“[...] This deal is needed now, because this is an issue of crucial importance for innovation and growth. I very much hope that the last outstanding issue will be sorted out at the May Competitiveness Council. If not, I will take it up at the June European Council.”

But IP matters will not become easier in Europe with Mr Hollande, given his apparent openness to positions of critics of the current patent system. In fact, some of the answers (pdf) of Ms Fleur Pellerin (@fleurpellerin), responsible for the digital economy in Hollande’s campaign team, on a tendentious pre-election questionnaire of French anti software patent group “April” appear as if the socialist candidate for president (or his spokeswoman) was one of the ideological leaders of that pressure group:

The patentability of software would induce a partitioning of innovation that would be harmful to the ecosystem seen in its digital together. I am therefore opposed to the patenting of software.

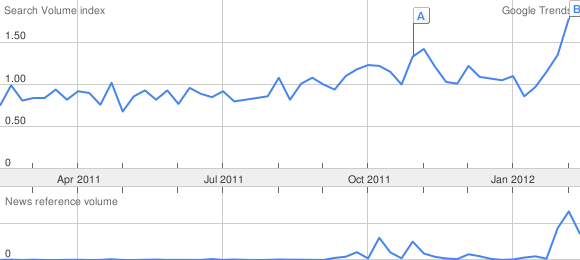

- Occurrence of the term “FRAND” in Google searches during the previous 12 months. In November 2011 (A) the EU Commission started investigations against Samsung due to possible infringement of FRAND conditions. In February 2012 (B) Google announced that the acquired Mororola patents will remain to be licensable under FRAND conditions.

In Part 1 of our series of two postings on political and business issues in the discussion on FRAND licensing in Europe, we sketched the EU Commission’s political approach towards maintaining free markets in times of standard-essential patents.

Now, in Part 2, we will have a closed look at what the various industry players in the ‘smartphone war’ say and do.

The ‘Smartphone War’: The significance of Mr Almunia’s agenda can be easily derived for the global patent conflict that initially started between Apple and Samsung and meanwhile, after months of infringement suits and injunctions, involves also essentially all other important Internet and mobile telco players such as Google, Motorola, Microsoft, Nokia and HTC. In an earlier posting we considered this to be a sort of stress test for the patent system as it currently is.

Warsaw, December 22, 2011: The Day Of Initialling The EU Unified Patent Court

Document 17539/11 authored by the Polish EU Presidency, titled Draft Agreement on the creation of a Unified Patent Court – Guidance for future work and directed to Permanent Representatives Committee ( COREPER Part 1) unveils under item 11 thereof:

The Presidency announced its intention to organise the initialling ceremony whereby the text of the Agreement could be finalised in Warsaw on 22 December 2011. The Presidency considers that the Member States should be able to arrive at a political agreement on the text of the Agreement at the meeting of the Competitiveness Council on 5 December 2011 on the basis of this set of compromise proposals, despite the fact that some issues of political importance could be left to be agreed at a later stage, but before the signature of the Agreement.

Well this appears to be quite big an issue. Why? Well, … in Document 16741/11 titled Draft agreement on a Unified Patent Court and draft Statute – Revised Presidency text we see current wording of Article 5 (1a) printed as follows:

(1a) The central division shall have its seat in [...]. The contracting Member State hosting the central division shall provide the necessary facilities for that purpose.

And, in a corresponding way, current wording of Article 7 (4) reads:

(4) The Court of Appeal shall have its seat in [...].

It is to be understood that the the initialling ceremony scheduled to happen in Warsaw on December 22 would be pointless if there isn’t a finalsed text of the entire Agreement ready for signing .. without those ellipsis in Articles 5 (1a) and 7 (4).

With other words: A political decision as to how to locate the seat of central portions of the UPC system is due to well ahead of the planned ceremony in Warsaw. For more details on the timetable, see also Volker Metzler’s post on visaepatentes.com.

Continue reading »

Yesterday the EPO News channel reported on a “renewed commitment to cost-efficient European patents” by the EPO and the European Commission. As nobody really had the slightest doubts on the continued and strong support by the project’s two main driving forces, this “news” does not sound that confident and persuasive as it apparenty was intended.

I cannot help, but to me it sounds more like political PR language or even autosuggestion if the President of the EPO, Benoît Battistelli, and the European Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services, Michel Barnier, jointly confess that “the unitary patent is [...] expected to simplify procedures and lower the costs for applicants by up to 70%“.

On September 2, 2011, the Polish EU Presidency submitted Document 13751/11 to the Friends of the Presidency Group titled Draft agreement on a Unified Patent Court and draft Statute – Revised Presidency text and originally marked as “LIMITE”, i.e. confidential. On September 23, 2011, another related Document 13751/11 COR 2 removed the “LIMITE” restriction from its parent document. However, Document 13751/11 COR 1 still appears not to be accessible at the time of writing this blog posting.

The history of the proceedings according to the narrative of the above-identified Document is that, following the discussions with Member States, the Polish Presidency has prepared a first set of amendments to the Draft Agreement on a Unified Patent Court and draft Statute covering up to Article 14d. The aim of this note is to explain the suggested changes and the envisaged way ahead. On June 14, 2011, the Hungarian Presidency had presented to the Mertens Group a modified Draft Agreement which confers exclusive jurisdiction upon a court common to the Member States in the field of European Patent and European Patent with unitary effect. This modified Draft Agreement was based on the previous draft agreement on the European and Community Patent Court and necessary amendments have been made to ensure compliance with the EU Treaties in response to the opinion 1/09 of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). It also included adaptations to the text in light of the December 2009 Council conclusions.

The introductory passage of the recently released Document explains the amendments done with regard to earlier versions as follows:

The main changes, which were proposed to ensure compliance with the EU Treaties as set out in the opinion of the CJEU were the limitation of participation in the draft agreement to EU Member States (thus excluding the participation of third states as well as the EU) and the strengthening of the obligation of the Unified Patent Court to comply with EU law and request preliminary rulings, if necessary, including through the introduction of sanctions. The removal from the draft of the EU and non-EU states as possible contracting parties fundamentally changed the nature of the Draft Agreement, the aim of which is to establish not just an international court, but a court common to the Member States. This will represent a new patent jurisdiction which will be an inherent part of the judicial systems of those Member States which are party to the agreement.

Continue reading »

Industrial Revolution 2.0: How the Material World Will Newly Materialize

3D printing is a form of additive manufacturing technology where a three-dimensional object is created by laying down successive layers of material. Since 2003 there has been large growth in the sale of 3D printers. Additionally, the cost of 3D printers has declined.

Just in these days and within the framework of the London Design Festival, the London Albert & Victoria Museum is staging an exhibition ‘Industrial Revolution 2.0: How the Material World will Newly Materialise’ . The exhibition is a showcase displaying works made by 3D printing by Stephen Jones, Patrick Jouin, Iris van Herpen, and many others. Renowned New York-based design gallerist and curator Murray Moss has collaborated with industry provider Materialise, Belgium to create a special exhibition which pushes the parameters of 21st century 3D printing. A series of unique ‘printed’ works, using cutting edge laser and digital technologies to build three-dimensional objects, are placed throughout the Museum’s most important galleries, wittily referencing eight of the Museum’s key pieces and spaces; see also this report on i.materialise.

With regard to patent law, 3D printing taken as such appears to bear no particular implications out of the normal routine: We may assume that professional providers like Materialise NV and others know what they are doing and have some legal or patent department giving suitable advice.

However, as 3D printing technologie gets mature, two developments are foreseeable:

- In a first stage, perhaps to be experienced in a few years of time, heavy-duty 3D printing equipment might be generally available but too expensive to be bought by broader consumer circles. Maybe that costs for such devices will be comparable to large professional photocopying machines. If such assumption should become reality, there might be room for new business models of 3D copy shops: Small businesses loacted in your town around next corner where you can show up with a memory stick or something like that storing a 3D model of some object you would like to have produced. Perhaps such shop even might provide 3D scanning services as well; in such case the customer simply shows up with some 3D object in his pocket and goes away with one or more exact replicas thereof.

- In a second stage, costs of 3D printing equipment might drop to levels comparable to today’s laser printer devices. Maybe that 3D printers will be heavily cross-subsidised by surcharges on printing raw materials in the same manner as 2D printers today are subsidised by expensive ink or toner cartridges. This would mean that consumers can produce a broad range of 3D objects at home without need to contract any external service provider.

Of course, there is some hype in the current reporting on 3D printing: For many practical applications, not only the 3D shape is of relevance but also more elaborate characteristics, e.g. in view of a specific electrical conductivity, hardness, heat-resistance and/or elasticity. Those who fear that in the age of 3D printing everyone might be able to produce firearms at home might be reminded that the functionality of a gun is not determined by its 3D shape alone; it must also bear the heat and the enormous forces of the explosion of the propellant.

But nevertheless surely there will be many useful real world applications of 3D printing, most of them perfectly legal, some, of course, blatantly illegal or serving illegal ends. There are, for example, reports saying criminals stole more than $400,000 using ATM skimming devices made from high-tech 3D printers.

But what we might see, if the above-noted assumptions are true, is that another front of legal battles will be opened where John Doe and Max Mustermann risk entanglement with Intellectual Property laws.

In the first half of the 20th century, virtually no private individual living a mainstream-style life ever was in risk of infringing copyright laws: Printing presses were as expensive as, later in the century, radio and TV broadcasting equipment and out of reach for private consumers. Mass media were, due to economic necessity, owned by larger corporations which could afford to take legal advice and which could held liable easily in case of wrongdoing.

But in the age of PCs connected to the Internet we today see an epic battle of rights holders attempting to defend and to enforce their exclusion rights in the field of Copyright in the courts against countless private individuals engaging e.g. in file-sharing activities at home on the basis of their own PC and Internet infrastructure.

The PC and the Internet are also the tools which even today might bring individuals in conflict with patents on computer-implemented inventions or software patents. However, contrary to many fears of open source advocates, up to now the mainstream of litigation e.g. in the smartphone patent litigation business is directed against major players in that market, not against more or less private individuals. Exceptions are a few commercial developers creating smartphone apps sued by Lodsys; however, the particulars of such cases appear to hint that the main direction of attack was meant to be platform providers like Apple or Google.

Things might again change in an age where 3D printing techniques have matured and are cheaply in everybody’s reach. 3D copy shops will probably not benefit from any exemptions in patent law privileging private and non-commercial use of patented technologies as they are present e.g. in national German patent law. I don’t talk here on patents covering the 3D scanning / printing processes and devices (these problems should be dealt with by the manufacturers of such equipment) but on patents (and, by the way, also registered designs) infringed not by the technology provided in the 3D printing shop but by the specific 3D objects or object models brought in by the non-commercial customers. Will rights holders attempt to shut down such small 3D copy shop businesses by filing lawsuits on the basis of secondary patent infringement? Anyway, consumer-oriented 3D copy shops would face utter difficulties in assessing if replicating some object brought in by a customer infringes third party’s IP rights if they were legally required to do so.

Even if the 3D technology gets operated at home by the consumer, problems remain. For example, the German patent exemption covers only acts that are cumulatively of private nature as well as non-commercial. Excange of money is not a necessary precondition to get out of the scope of this exemption. For example, producing a small lot of object for free distribution amongst friends might, under some circumstances, be considered lying outside the scope of the German private-use patent infringement exemption.

Will we see in, say 10 years from now, a discussion on liability of ISPs for not filtering out 3D model data utilisable for 3D printing if they are suspected of infringing patent / design rights?

How (Not) To Get Rid Of Software Patents

Today we have seen general elections to the Berlin City Parliament. Perhaps you may know that Berlin is not only a big city with some 3.5 Million inhabitants which also is the capital of Germany. In addition, Berlin constitutes one of the 16 states of Germany. Hence, Berlin City Parliament plays its role not only in the context of the City but also with regard to the federal structure of Germany.

At the time of writing of this posting, exit polls show that the Berlin chapter of the German Pirate Party will surpass the 5% quorum by a quite sensational 8-9% share on votes. This result shows that the mood especially of younger voters and first time voters is changing, moving away from all of the established parties including the Greens and the Left (Die Linke). At the occasion of the last Germany-wide general elections to the federal parliament in September 2009, the Pirate Party had got less than 2% of the votes. Many voters are reluctant to cast their vote for any party that is well below the 5% hurdle because of the high probability that voting for such party has no power to change anything. However, now, after the Berlin chapter of the German Pirate Party not only got over the 5% quorum by some narrow margin but obtained a sensational surplus of up to 4 percent points over the 5% hurdle, such reservations dwindle and, hence, I expect to see them in more State Parliaments of other Bundesländer in the coming years. And, like it or not, taking the history of the other German grassroots party, the Greens, as a precedent, the Pirates might well sit in the lower chamber Bundestag of the German Parliament in 2017 if they miss the 5% hurdle in the next general elections scheduled for fall 2013.

What does this mean with regard to Intellectual Property politics and business?

Continue reading »

Back in September 2010 the EPO-sponsored 15th European Patent Judge’s Symposium took place in Lisbon, where the judges discussed developments in European patent law. The symposium was attended by 120 patent judges from Europe and guests from the USA and Japan. A big issue of course was the EU patent and the related litigation system, but the related discussion is now meaningless in view of the recent developments in this regard. But there were other interesting topics discussed as well.

For instance, in a working session on “Patentability of Computer implemented inventions”, Mr. Dai Rees – Chairman of an EPO appeal board and member of the Enlarged Board of Appeals that issued the G3/08 opinion – outlined the developments of the respective EPO case law. His contribution is documented in an article in the conference proceedings: Special edition 1/2011 of EPO Office Journal (PDF, 5 MB), pp. 93 to 102. The below summary reflects my personal observations and understanding of Mr. Rees presentation and also contains some individual flavours and thoughts.

Relevant Provisions: As a reminder, the provisions of the EPC to be considered for computer programs or technicality issues not only involve Art 52 EPC (“programs for computers as such“), but also Articles 18, 19, 21, 22 and Rules 42(1)(a), (c), 43(1) and 44 EPC, which use the term “technical” in different contexts. Further, in the EPC 2000 revision, Art 52(1) EPC was clarified in that patents shall be granted for inventions “in all fields of technology”, which, however, was regarded as a clarification rather than a substantive amendment of the Convention.

The k/s/n/h::law blog

Some of the patent attorneys of the KSNH law firm have joined their efforts to research what is going on in the various branches of IP law and practice in order to keep themselves, their clients as well as interested circles of the public up to date. This blog is intended to present results of such efforts to a wider public.

Blog Archives

- November 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (5)

- March 2013 (5)

- February 2013 (4)

- January 2013 (5)

- December 2012 (5)

- November 2012 (5)

- July 2012 (5)

- June 2012 (8)

- May 2012 (5)

- April 2012 (3)

- March 2012 (4)

- February 2012 (5)

- January 2012 (6)

- December 2011 (12)

- November 2011 (9)

- October 2011 (9)

- September 2011 (4)

- August 2011 (7)

- July 2011 (4)

- June 2011 (1)

Blog Categories

- business methods (6)

- EPC (7)

- EPO (12)

- EU law (92)

- ACTA (8)

- CJEU (4)

- Comitology (1)

- competition law (2)

- Enforcement (6)

- EU Unified Patent Court (62)

- FTA India (1)

- TFEU (2)

- Trade Marks (5)

- European Patent Law (37)

- German Patent ACt (PatG) (1)

- German patent law (5)

- Germany (6)

- Pirate Party (3)

- International Patent Law (4)

- PCT (2)

- IP politics (10)

- licenses (2)

- Litigation (5)

- Patentability (7)

- Patents (12)

- Piratenpartei (2)

- Software inventions (10)

- Uncategorized (9)

- Unitary Patent (24)

- US Patent Law (4)

Comments

- kelle on Germany: Copyright Protection More Easily Available For Works Of “Applied Arts”

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days - KSNH Law - Intangible.Me on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days | ksnh::law on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Cou... on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- European Commission Takes Next Step Towards Legalising Software Patents in Europe | Techrights on EU Commission publishes Proposal of amendend Brussels I Regulation for ensuring Enforcement of UPC Judgements

Blogroll

- 12:01 Tuesday

- America-Israel Patent Law

- Anticipate This!

- AwakenIP

- BlawgIT

- BLOG@IPJUR.COM

- BP/G Radio Intellectual Property Podcast

- Broken Symmetry

- Class 46

- Director's Forum: David Kappos' Public Blog

- Gray on Claims

- I/P UPDATES

- IAM Magazine Blog

- Intellectual Property Intelligence Blog

- IP Asset Maximizer Blog

- IP CloseUp

- IP Dragon

- IP Watch

- IP Watchdog

- IPBIZ

- ipeg

- IPKat

- ITC 337 Law Blog

- Just a Patent Examiner

- K's Law

- MISSION INTANGIBLE

- Patent Baristas

- Patent Circle

- Patent Docs

- Patently Rubbish

- PatentlyO

- Patents Post-Grant

- Reexamination Alert

- SPICY IP

- Tangible IP

- The 271 Patent Blog

- The Intangible Economy

- THE INVENT BLOG®

- Think IP Strategy

- Tufty the Cat

- Visae Patentes

The KSNH blogging landscape

This blog and the German-language sister blog k/s/n/h::jur link to the two popular and privately run blogs IPJur und VisaePatentes and continue their work and mission with a widened scope and under the aegis of our IP law firm.

ksnhlaw on Twitter

- No public Twitter messages.

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013Auf verschiedenen Feldern beruflicher Praxis ist dafür zu sorgen, dass Kommunikation vertraulich bleibt. Die trifft beispielsweise für Ärzte zu, aber auch für Anwälte, darunter auch Patentanwälte. Einer der zahlreichen Aspekte, die in diesem Zusammenhang eine Rolle spielen, ist die Technik, um die Vertraulichkeit beruflicher Kommunikation sicherzustellen. Wa […]

- EU-Einheitspatent: Demonstrativer Optimismus und Zahlenmystik allerorten – Naivität oder politische Beeinflussung? June 26, 2013Nach mehreren vergeblichen Anläufen zur Schaffung eines EU-weiten Patentsystems wurde 1973 als Kompromiss das Europäische Patentübereinkommen unterzeichnet, welches unabhängig von der seinerzeit noch EWG genannten Europäischen Union System zur zentralisierten Patenterteilung mit nachgeordnetem Einspruchsverfahren durch das Europäische Patentamt schuf. Wie wi […]

- Moderne Zeiten oder: DPMA und Patentgericht streiten über die elektronische Akte April 25, 2013Bekanntlich hat das Deutsche Patent- und Markenamt (DPMA) im Jahre 2013 mit der rein technischen Fertigstellung der Einrichtungen zur elektronischen Akteneinsicht einen wichtigen Meilenstein seines Überganges von der Papierakte zur “elektronischen Akte” erreicht. Im DPMA werden aber bereits seit dem 01. Juni 2011 Patente, Gebrauchsmuster, Topografien und erg […]

- Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013 March 11, 2013Unter dem Datum vom 28. Februar 2013 ist die Bundestags-Drucksache 17/12611 veröffentlicht worden Sie trägt den Titel Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung - Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013. Die Bundesregierung legt dem Deutschen Bundestag seit dem Jahr 2008 […]

- 3D-Printing: Zum Filesharing von 3D-Modelldaten February 25, 2013In meiner kleinen zuvor angekündigten Reihe über rechtliche Aspekte des 3D Printing komme ich heute auf die Frage zu sprechen, ob die Hersteller von Gerätschaften es hinnehmen müssen, wenn Ersatztreile davon – vom Brillengestell über Smartphone-Gehäuseteile bis hin zu Rastenmähermotor-Abdeckungen – gescannt und die daraus […]

- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013