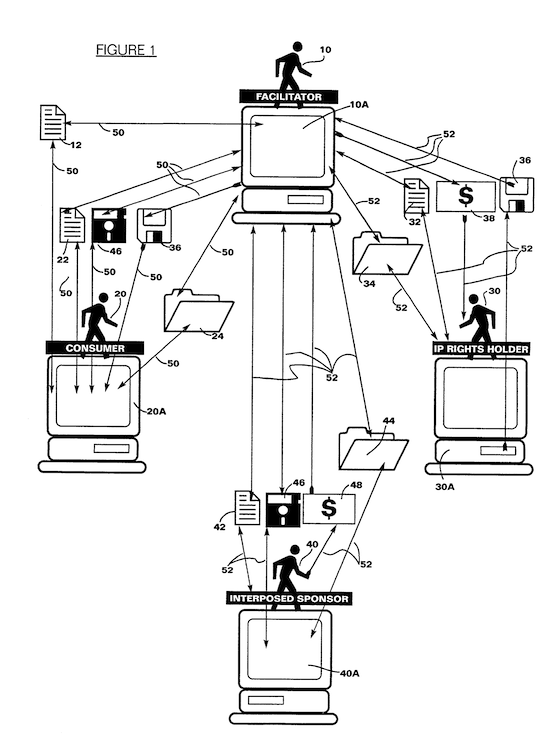

The patent US 7,346,545, relating to delivering copyrighted media products through a server free of charge in exchange for watching advertisements, has been enforced by Ultramercial against a number of Internet media competitors, like Hulu, WildTangent and YouTube. In August 2010 the 545 patent has been found invalid by a California District Court in view of the Bilski v. Kappos ruling which has been issued shortly before by the US Supreme Court (CV 09-06918). For further information on this case, please see my earlier posting here.

The patent US 7,346,545, relating to delivering copyrighted media products through a server free of charge in exchange for watching advertisements, has been enforced by Ultramercial against a number of Internet media competitors, like Hulu, WildTangent and YouTube. In August 2010 the 545 patent has been found invalid by a California District Court in view of the Bilski v. Kappos ruling which has been issued shortly before by the US Supreme Court (CV 09-06918). For further information on this case, please see my earlier posting here.

To be on the safe side, the District Court applied a two-stage approach, that is, as a screening filter, the CAFC’s machine-or-transformation test and then the SCOTUS abstract idea test.

The MOT test failed as the District Court found that the “mere act of storing media on computer memory does not tie the invention to a machine in any meaningful way”. Further, the Court identified “using advertisement as a currency” as the core principle of the patent, while the claims do not cite any concrete features as to how the core principle can be implemented.

Some observers criticised the District Court’s reasoning as being capable to kill any invention where a key concept can be labelled ‘abstract’ even if the invention is clearly limited to an electronic implementation and even if the electronic implementation is central to the idea.

Now, as the Federal Circuit under Chief Judge Radar reviewed the case in appeal, it turns out that such criticism hit the mark (see decision of June 21, 2013), as the case was reversed and remanded. In its decision the Federal Circuit referred multiple times to the term “technology”, e.g.:

- The plain language of the [patent act] provides that any new, non-obvious, and fully disclosed technical advance is eligible for protection.

- After all, unlike the Copyright Act which divides ideas from expression, the Patent Act covers and protects any new and useful technical advance, including applied ideas.

- Far from abstract, advances in computer technology—both hardware and software—drive innovation in every area of scientific and technical endeavor.

In this ealier posting on the America Invents Act we reported on the new Covered Business Methods Review (faq, info) which allows to challenge any business method patent before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as soon as it is enforced against an accused infringer.

In this ealier posting on the America Invents Act we reported on the new Covered Business Methods Review (faq, info) which allows to challenge any business method patent before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) as soon as it is enforced against an accused infringer.

From a European perspective, this new proceedings seems particularly interesting as the question as to whether or not a claim falls under the CBM review is answered by 37 CFR § 42.301 as follows:

(a) Covered business method patent means a patent that claims a method or corresponding apparatus for performing data processing or other operations used in the practice, administration, or management of a financial product or service, except that the term does not include patents for technological inventions.

(b) Technological invention. In determining whether a patent is for a technological invention solely for purposes of the Transitional Program for Covered Business Methods (section 42.301(a)), the following will be considered on a case-by-case basis: whether the claimed subject matter as a whole recites a technological feature that is novel and unobvious over the prior art; and solves a technical problem using a technical solution.

This definition is surprisingly similar to what European case law (and German case law) has developed to define “methods for [...] doing business [...] and programs for computers as such” according to Art. 52 (2), (3) EPC (and § 1 (3), (4) PatG). Even further, the requirement of a “technological feature that is novel and unobvious” seems to correspond to the well-established Comvik approach (cf. T 641/00, 2002) of the EPO Boards of Appeal, according to which non-technical features cannot contribute to novelty and inventive step.

On an Official blog website blogfraktion.de of the parliamentary group of the Christian Democratic Union / Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) in the German Bundestag I recently stumbled upon a green paper concerning copyright in the digital society (Diskussionspapier der CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion zum Urheberrecht in der digitalen Gesellschaft) presented by Deputy Party Whips Mr Michael Kretschmer and Mr Günter Krings. While the main topic of this text, of course, is directed to copyright issues, we also can find a single paragraph devoted to so-called software patents or, more technically, patents on computer-implemented (respectively implementable) inventions as follows (I did some plain copy/paste operation and refrain from correcting spelling errors in the German original):

8. Urheberrecht statt Softwarepatenten

Computerprogramme werden richtigerweise durch das Urheberrecht geschützt. „Softwarepatente“ auf Quell-Codes laufen dem urheberrechtlichen Schutzzweck zuwider. Der urheberrechtliche Schutz ist flexibler und innovationsfördernder, weil dazu kein aufwendiges und teures Patentierungsverfahren notwendig ist. Die Anwendbarkeit des Urhebervertragsrechts stärkt außerdem die Programmierer (Urheber) gegenüber den Softwarefirmen (Verwertern).

Ein Richtlinienvorschlag der EU-Kommission, eine EU-einheitliche Patentierungspraxis für Software zu schaffen, ist 2002 gescheitert. Die CDU/CSU-Bundestagsfraktion lehnt auch weiterhin jede Ausweitung der Patentierungspraxis im Softwarebereich ab.

I would like to offer my own translation as set out below:

8. Copyright instead of software patents

Computer programs are rightly protected by copyright. “Software patents” on source code run contrary to the purpose of protection by copyright. Protection by copyright is more flexible and encourages innovation more because it does not require intricate and expensive patenting proceedings. Moreover, the applicability of the [German] law of contracts on copyrights strengthens the coders (creators) compared to software companies (exploiters).

A Draft proposal of the EU Commission for creating a unitary practice of patenting of software has failed in 2002. The parliamentary group of the CDU/CSU in the Bundestag maintain their rejection of any broadening of the practice of patenting in the field of software.

The first sentence of this statement asserting that computer programs are rightly protected by copyright is one of the few snippets of information from the text as quoted above which is by and large correct insofar historically the Council Directive 91/250/EEC of 14 May 1991 on the legal protection of computer programs had stipulated in its Article 1 that Member States shall protect computer programs, by copyright, as literary works within the meaning of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works. However, the term “rightly” (“richtigerweise” in German) might, at least for German ears, be construed like suggesting that software protection by copyright is the only (proper and legitimate) way to define software-related Intellectual Property. This is not true. Article 9 paragraph 1 of the Directive says (emphasis added):

The provisions of this Directive shall be without prejudice to any other legal provisions such as those concerning patent rights, trade-marks, unfair competition, trade secrets, protection of semi-conductor products or the law of contract. [...]

In the next sentence: “Software patents” on source code run contrary to the purpose of protection by copyright, a stark theory is proclaimed deepening this initial stub of mis-understanding the law by setting forth in more detail there is sort of a contradiction between copyright and patent law. In fact, copyright law and patent law are mapped to different aspects of computer software, respectively:

- From a copyright-centred point of view, a computer program is seen as a text (source code).

- From a patent-centred point of view, a computer program is seen as an expression of functionality or of dynamic semantics described by operational and/or denotational semantics, i.e. it is viewed as an expression of run-time behaviour.

Copyright and patent rights can emerge from one and the same set of facts of a case. This phenomenon is not confined to copyright and patent law concerning software. Take, for example, a mud wing of a car:

Continue reading »

Anti-Patent Campaigners put their trust in François Hollande as EU Council attends to Unitary Patent Court again

The newly elected President of France, François Hollande promising "change". Will he be the first anti-patent campaigner governing an EU state?

Now that François Hollande took office as the new President of France after his marginal victory in the French presidential elections this May, he will now introduce himself to official EU policy on his first Competitive Council meeting on May 31/June 1. The draft agenda for this meeting (cf. item 19), reading “Draft agreement on a Unified Patent Court and draft Statute – Political agreement“, electrifies observers of and parties involved the ongoing European patent legislation saga (see also press release, middle of page 5).

In recent months the upcoming French elections brought the negotiations on the Unified Patent Court Agreement to a complete standstill, as the dynamics between the French, British and German heads of govenment and the general political climate is a crucial factor in this legislative process, especially since the only serious and realistic candidates for the attractive seat of the new UPC Central Division are Paris, London, and Munich and it is frequently announced through official channels that this question is the only remaining open issue.

The EU Council expressed already in January this year its believe that a final agreement can be reached in June 2012 (see official statement) and it was the President of the European Council, Herman Van Rompuy, who clarified in a recent letter that he hopes (or expects) the remaining issues to be sorted out at next week’s Competitiveness meeting:

“[...] This deal is needed now, because this is an issue of crucial importance for innovation and growth. I very much hope that the last outstanding issue will be sorted out at the May Competitiveness Council. If not, I will take it up at the June European Council.”

But IP matters will not become easier in Europe with Mr Hollande, given his apparent openness to positions of critics of the current patent system. In fact, some of the answers (pdf) of Ms Fleur Pellerin (@fleurpellerin), responsible for the digital economy in Hollande’s campaign team, on a tendentious pre-election questionnaire of French anti software patent group “April” appear as if the socialist candidate for president (or his spokeswoman) was one of the ideological leaders of that pressure group:

The patentability of software would induce a partitioning of innovation that would be harmful to the ecosystem seen in its digital together. I am therefore opposed to the patenting of software.

During the past 15 years the Boards of Appeal of the EPO have developed a consistent case law as to the pragmatic problem/solution approach for assessing patentability pursuent Art 52 -57 EPC. In our earlier overview on

EPO case law regarding patentability of software inventions,

to which this posting is meant as a more practical continuation, we briefly characterised the EPO’s main examination approach:

[M]odern case law [of the EPO Boards of Appeal on software inventions], especially the suggestion in T 1173/97 that the “technical contribution” is an inventive step consideration and the observation in some early cases (e.g. T 38/86 and T 65/86) that the “inventive contribution” must lie in a “field of technology”, almost naturally lead to the problem-solution approach as developed in T 641/00 (COMVIK) and T 258/03 (Hitachi) and theoretically justified in T 154/04 (Duns).

This approach nowadays is the crucial test to differentiate between a technical contribution implementing a non-technical concept (e.g. a business method) and an inventive contribution in a technical field (e.g. an embedded control software). Its general idea is that only the technical features of a claim may be taken into account for assessing inventive step, while the non-technical features form a basis for formulating the underlying problem, with the effect that the non-technical features may render the technical solution obvious.

This approach is widely accepted among practitioners as enhancing legal security for applicants since it represents a comprehensible benchmark against which EPO decisions are subject to verifiction.

How (Not) To Get Rid Of Software Patents

Today we have seen general elections to the Berlin City Parliament. Perhaps you may know that Berlin is not only a big city with some 3.5 Million inhabitants which also is the capital of Germany. In addition, Berlin constitutes one of the 16 states of Germany. Hence, Berlin City Parliament plays its role not only in the context of the City but also with regard to the federal structure of Germany.

At the time of writing of this posting, exit polls show that the Berlin chapter of the German Pirate Party will surpass the 5% quorum by a quite sensational 8-9% share on votes. This result shows that the mood especially of younger voters and first time voters is changing, moving away from all of the established parties including the Greens and the Left (Die Linke). At the occasion of the last Germany-wide general elections to the federal parliament in September 2009, the Pirate Party had got less than 2% of the votes. Many voters are reluctant to cast their vote for any party that is well below the 5% hurdle because of the high probability that voting for such party has no power to change anything. However, now, after the Berlin chapter of the German Pirate Party not only got over the 5% quorum by some narrow margin but obtained a sensational surplus of up to 4 percent points over the 5% hurdle, such reservations dwindle and, hence, I expect to see them in more State Parliaments of other Bundesländer in the coming years. And, like it or not, taking the history of the other German grassroots party, the Greens, as a precedent, the Pirates might well sit in the lower chamber Bundestag of the German Parliament in 2017 if they miss the 5% hurdle in the next general elections scheduled for fall 2013.

What does this mean with regard to Intellectual Property politics and business?

Continue reading »

Software Patent Litigation: Stress Testing The Patent System

As we know from Wikipedia, stress testing is a form of testing that is used to determine the stability of a given system or entity. It involves testing beyond normal operational capacity, often to a breaking point, in order to observe the results. The concept is quite fashionable nowadays; it has reached mainstream in the context of the financial sector and even when making an assessment of operational characteristics of a railway station.

Now it looks as if we shall be witnesses of something that comes near to a major stress testing exercise of the patent system.

We all are supposed to be aware that an awful lot of litigation is currently going on in the field of mobile devices like smartphones and tablet computers. Reuters have published nice infographics on patent-related suits between mobile device / component manufacturers here. Moreover, there are press reports saying that Apple, Inc., is about to launch another patent based suit against Samsung allegedly aiming at a EU wide ban on all of Samsung’s smartphones and tablet computers under its Galaxy brand. If these speculations were true and if Apple were to prevail in such battle, the suit could not only be a blow to Samsung but also to the Android ecosystem in its entirety.

Another litigation front has been opened by a company named Lodsys, a non-pracitcing entity (NPE) suing certain individual software developers who brought to market smartphone apps which allegedly are infringing Lodsys’ patent rights.

It appears to be quite clear that the motivation of Google to acquire Motorola Mobility for USD 12,5 billion is mostly fueled by their desire to overcome a perceived inferiority of their own patent portfolio.

Back in September 2010 the EPO-sponsored 15th European Patent Judge’s Symposium took place in Lisbon, where the judges discussed developments in European patent law. The symposium was attended by 120 patent judges from Europe and guests from the USA and Japan. A big issue of course was the EU patent and the related litigation system, but the related discussion is now meaningless in view of the recent developments in this regard. But there were other interesting topics discussed as well.

For instance, in a working session on “Patentability of Computer implemented inventions”, Mr. Dai Rees – Chairman of an EPO appeal board and member of the Enlarged Board of Appeals that issued the G3/08 opinion – outlined the developments of the respective EPO case law. His contribution is documented in an article in the conference proceedings: Special edition 1/2011 of EPO Office Journal (PDF, 5 MB), pp. 93 to 102. The below summary reflects my personal observations and understanding of Mr. Rees presentation and also contains some individual flavours and thoughts.

Relevant Provisions: As a reminder, the provisions of the EPC to be considered for computer programs or technicality issues not only involve Art 52 EPC (“programs for computers as such“), but also Articles 18, 19, 21, 22 and Rules 42(1)(a), (c), 43(1) and 44 EPC, which use the term “technical” in different contexts. Further, in the EPC 2000 revision, Art 52(1) EPC was clarified in that patents shall be granted for inventions “in all fields of technology”, which, however, was regarded as a clarification rather than a substantive amendment of the Convention.

Amazon’s One-Click Patent in Europe and Elsewhere

Amazon’s so called “One-Click Patent” is one of the most controversially discussed software inventions ever. The term, which nowadays is used as a cipher for a prototypical business method patent, was originally coined for US 5,960,411 titled “method and system for placing a purchase order via a communications network” (filed 12 Sep 2007, granted 28 Sep 1999; pdf), which has been enforced against competitor Barnes & Noble and licensed to Apple.

Amazon’s so called “One-Click Patent” is one of the most controversially discussed software inventions ever. The term, which nowadays is used as a cipher for a prototypical business method patent, was originally coined for US 5,960,411 titled “method and system for placing a purchase order via a communications network” (filed 12 Sep 2007, granted 28 Sep 1999; pdf), which has been enforced against competitor Barnes & Noble and licensed to Apple.

The respective teaching enables easy Internet shopping in that a customer visits a website, enters address and payment information and is associated with an identifier stored in a “cookie” in his client computer. A server is then able to recognize the client by the cookie and to retrieve purchasing information related to the customer, who thus can buy an item with a “single click”.

EP Parent Application: The first “1-click” application in Europe, EP 0 909 381 A2, related to an Internet-based customer data system and claimed a “method for ordering an item using a client system“. The application has been withdrawn on 08 June 2001 in view of approaching oral proceedings that had been summoned by the Examining Division with a negative preliminary opinion saying that the claimed teaching was not inventive over prior art document D3 (Baron C: “Implementing a Web shopping cart”, Dr. Dobbs Journal, Redwood City, CA, 01.09.1997). During the proceedings, Dutch Internet bookseller BOL.COM supported the Examining Division by a number of third party observations according to Art. 115 EPC, all of which pointing the Examining Division to the relevance of D3 (see e.g. here or here).

I. RECENT CASE LAW

In the past two years we have seen a number of quite interesting decisions of the German Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof; BGH) dealing with patent-eligibility of software-related inventions.

The first decision in the row was X ZB 22/07 („Steuerung für Untersuchungsmodalitäten“, “Control of Examination Modalities”) of 20 January 2009, in which the BGH analysed the circumstances under which an embedded software represents statutory subject-matter (see comments). In this decision the BGH sketched a two-step approach to examine whether or not an invention is sufficiently “technical” to qualify for patent eligibility:

- Is the subject-matter a “technical invention” as required by § 1 I PatG ?

- Does the invention fall under the exclusion of a “computer programs as such” as requited by § 1 III No. 3, IV PatG ?

An additional third step completes the examination scheme:

- Do the technical features render the invention novel and inventive over prior art?

The k/s/n/h::law blog

Some of the patent attorneys of the KSNH law firm have joined their efforts to research what is going on in the various branches of IP law and practice in order to keep themselves, their clients as well as interested circles of the public up to date. This blog is intended to present results of such efforts to a wider public.

Blog Archives

- November 2013 (2)

- October 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (2)

- July 2013 (3)

- June 2013 (5)

- March 2013 (5)

- February 2013 (4)

- January 2013 (5)

- December 2012 (5)

- November 2012 (5)

- July 2012 (5)

- June 2012 (8)

- May 2012 (5)

- April 2012 (3)

- March 2012 (4)

- February 2012 (5)

- January 2012 (6)

- December 2011 (12)

- November 2011 (9)

- October 2011 (9)

- September 2011 (4)

- August 2011 (7)

- July 2011 (4)

- June 2011 (1)

Blog Categories

- business methods (6)

- EPC (7)

- EPO (12)

- EU law (92)

- ACTA (8)

- CJEU (4)

- Comitology (1)

- competition law (2)

- Enforcement (6)

- EU Unified Patent Court (62)

- FTA India (1)

- TFEU (2)

- Trade Marks (5)

- European Patent Law (37)

- German Patent ACt (PatG) (1)

- German patent law (5)

- Germany (6)

- Pirate Party (3)

- International Patent Law (4)

- PCT (2)

- IP politics (10)

- licenses (2)

- Litigation (5)

- Patentability (7)

- Patents (12)

- Piratenpartei (2)

- Software inventions (10)

- Uncategorized (9)

- Unitary Patent (24)

- US Patent Law (4)

Comments

- kelle on Germany: Copyright Protection More Easily Available For Works Of “Applied Arts”

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days - KSNH Law - Intangible.Me on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Time Limits & Deadlines in Draft UPCA RoP: Counting The Days | ksnh::law on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Cou... on Wiki Edition of Agreement on Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA)

- European Commission Takes Next Step Towards Legalising Software Patents in Europe | Techrights on EU Commission publishes Proposal of amendend Brussels I Regulation for ensuring Enforcement of UPC Judgements

Blogroll

- 12:01 Tuesday

- America-Israel Patent Law

- Anticipate This!

- AwakenIP

- BlawgIT

- BLOG@IPJUR.COM

- BP/G Radio Intellectual Property Podcast

- Broken Symmetry

- Class 46

- Director's Forum: David Kappos' Public Blog

- Gray on Claims

- I/P UPDATES

- IAM Magazine Blog

- Intellectual Property Intelligence Blog

- IP Asset Maximizer Blog

- IP CloseUp

- IP Dragon

- IP Watch

- IP Watchdog

- IPBIZ

- ipeg

- IPKat

- ITC 337 Law Blog

- Just a Patent Examiner

- K's Law

- MISSION INTANGIBLE

- Patent Baristas

- Patent Circle

- Patent Docs

- Patently Rubbish

- PatentlyO

- Patents Post-Grant

- Reexamination Alert

- SPICY IP

- Tangible IP

- The 271 Patent Blog

- The Intangible Economy

- THE INVENT BLOG®

- Think IP Strategy

- Tufty the Cat

- Visae Patentes

The KSNH blogging landscape

This blog and the German-language sister blog k/s/n/h::jur link to the two popular and privately run blogs IPJur und VisaePatentes and continue their work and mission with a widened scope and under the aegis of our IP law firm.

ksnhlaw on Twitter

- No public Twitter messages.

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)

KSNH::JUR Feed (german)- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013Auf verschiedenen Feldern beruflicher Praxis ist dafür zu sorgen, dass Kommunikation vertraulich bleibt. Die trifft beispielsweise für Ärzte zu, aber auch für Anwälte, darunter auch Patentanwälte. Einer der zahlreichen Aspekte, die in diesem Zusammenhang eine Rolle spielen, ist die Technik, um die Vertraulichkeit beruflicher Kommunikation sicherzustellen. Wa […]

- EU-Einheitspatent: Demonstrativer Optimismus und Zahlenmystik allerorten – Naivität oder politische Beeinflussung? June 26, 2013Nach mehreren vergeblichen Anläufen zur Schaffung eines EU-weiten Patentsystems wurde 1973 als Kompromiss das Europäische Patentübereinkommen unterzeichnet, welches unabhängig von der seinerzeit noch EWG genannten Europäischen Union System zur zentralisierten Patenterteilung mit nachgeordnetem Einspruchsverfahren durch das Europäische Patentamt schuf. Wie wi […]

- Moderne Zeiten oder: DPMA und Patentgericht streiten über die elektronische Akte April 25, 2013Bekanntlich hat das Deutsche Patent- und Markenamt (DPMA) im Jahre 2013 mit der rein technischen Fertigstellung der Einrichtungen zur elektronischen Akteneinsicht einen wichtigen Meilenstein seines Überganges von der Papierakte zur “elektronischen Akte” erreicht. Im DPMA werden aber bereits seit dem 01. Juni 2011 Patente, Gebrauchsmuster, Topografien und erg […]

- Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013 March 11, 2013Unter dem Datum vom 28. Februar 2013 ist die Bundestags-Drucksache 17/12611 veröffentlicht worden Sie trägt den Titel Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung - Gutachten zu Forschung, Innovation und technologischer Leistungsfähigkeit Deutschlands 2013. Die Bundesregierung legt dem Deutschen Bundestag seit dem Jahr 2008 […]

- 3D-Printing: Zum Filesharing von 3D-Modelldaten February 25, 2013In meiner kleinen zuvor angekündigten Reihe über rechtliche Aspekte des 3D Printing komme ich heute auf die Frage zu sprechen, ob die Hersteller von Gerätschaften es hinnehmen müssen, wenn Ersatztreile davon – vom Brillengestell über Smartphone-Gehäuseteile bis hin zu Rastenmähermotor-Abdeckungen – gescannt und die daraus […]

- Ist Verschlüsselung passé? September 6, 2013